I’ve had some wonderful interlocutors lately. One (in private, and therefore anonymously) has recommended Don Ihde’s postphenomenology of science. I’ve been reading and enjoying Ihde’s Instrumental Realism (1991) and finding it very fruitful. Ihde is influential in some contemporary European theories of the interaction between law and technology. Tapan Parikh has (on Twitter) asked me why I haven’t been engaging more with Agre (e.g., 1997). I’ve been reminded by him and others of work in “critical HCI”, a field I encountered a lot in graduate school, which has its roots in, perhaps, Suchman (1987).

I don’t like and have never liked critical HCI and have resented its pretensions of being “more ethical” than other fields of technological design and practice for many years. I state this as a psychological fact, not as an objective judgment of the field. This morning I’m taking a moment to meditate on why I feel this way, and what that means for my work.

Agre (1997) has some telling anecdotes about being an AI researcher at MIT and becoming disillusioned upon encountering phenomenology and ethnomethodological work. His problem began with a search for originality.

My college did not require me to take many humanities courses, or learn to write in a professional register, and so I arrived in graduate school at MIT with little genuine knowledge beyond math and computers. …

My lack of a liberal education, it turns out, was only half of my problem. Only much later did I understand the other half, which I attribute to the historical constitution of AI as a field. A graduate student is responsible for finding a thesis topic, and this means doing something new. Yet I spent much of my first year, and indeed the next couple of years after my time away, trying very hard in vain to do anything original. Every topic I investigated seemed driven by its own powerful internal logic into a small number of technical solutions, each of which had already been investigated in the literature. …

Often when I describe my dislike for e.g. Latour, people assume that I’m on a similar educational path to Agre’s: that I am a “technical person”, perhaps with a “mathematical mind”, that I’ve never encountered any material that would challenge what has now solidified as the STEM paradigm.

That’s a stereotype that does not apply to me. For better or for worse, I had a liberal arts undergraduate education with exposure to technical subjects, social sciences, and the humanities. My graduate school education was similarly interdisciplinary.

There are people today who are advocates of critical HCI and design practices in the tradition of Suchman, Agre, and so on that have a healthy exposure to STEM education. There are also many who do not and employ this material as a kind of rear guard action to treat any less “critical” work as intrinsically tainted with the same hubris that the AI field did in, say, the 80’s. This is ahistorical and deeply frustrating. These conversations tend to end when the “critical” scholar insists on the phenomenological frame–arguing either implicitly or explicitly that (post-)positivism is unethical in and of itself.

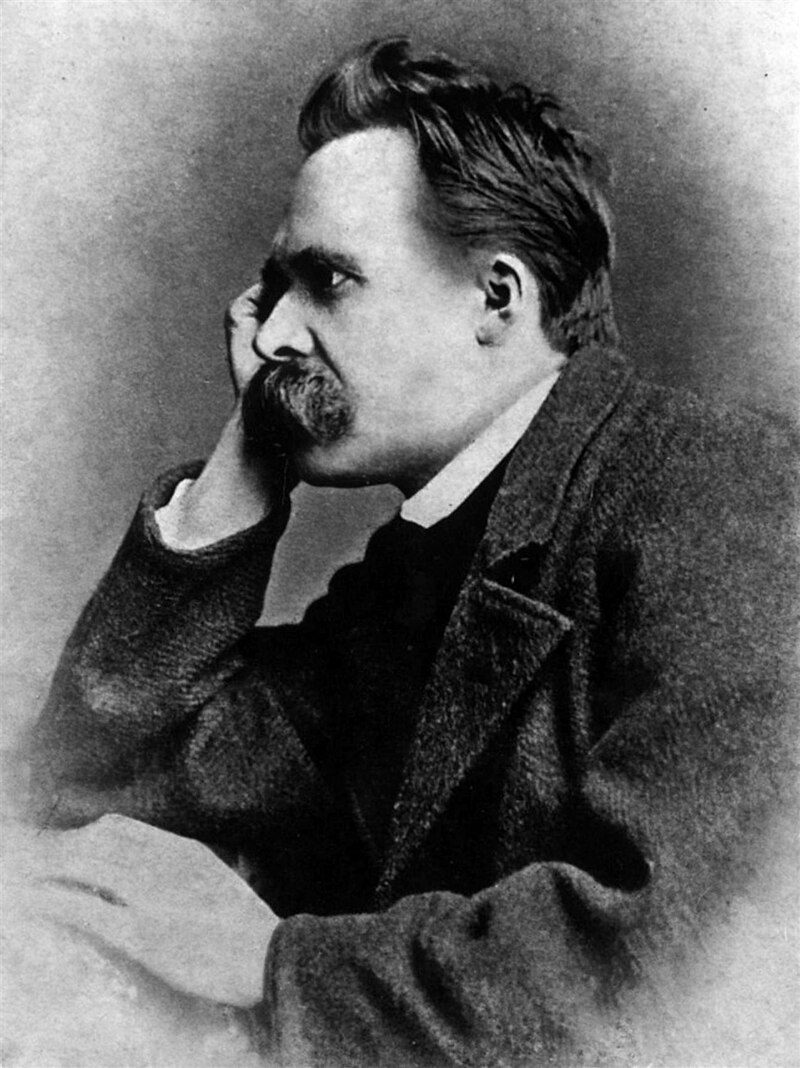

It’s worth tracing the roots of this line of reasoning. Often, variations of it are deployed rhetorically in service of the cause of bringing greater representation of marginalized people into the field of technical design. It’s somewhat ironic that, as Duguid (2012) helpfully points out, this field of “critical” technology studies, drawing variously on Suchman, Dreyfus, Agre, and ultimately Latour and Woolgar, is ultimately Heidegger. Heidegger’s affiliation with Nazism is well-known, boring, and in no way a direct refutation of the progressive deployments for critical design.

But back to Agre, who goes on to discuss his conversion to phenomenology. Agre’s essay is largely an account of his rejection of the project of technical creation as a goal.

… I was unable to turn to other, nontechnical fields for inspiration. … The problem was not exactly that I could not understand the vocabulary, but that I insisted on trying to read everything as a narration of the workings of a mechanism. By that time much philosophy and psychology had adopted intellectual styles similar to that of AI, and so it was possible to read much that was congenial — except that it reproduced the same technical schemata as the AI literature. …

… I was also continually noticing the many small transformations that my daily life underwent as a result of noticing these things. As my intuitive understanding of the workings of everyday life evolved, I would formulate new concepts and intermediate on them, whereupon the resulting spontaneous observations would push my understanding of everyday life even further away from the concepts that I had been taught. … It is hard to convey the powerful effect that this experience had upon me; my dissertation (Agre 1988), once I finally wrote it, was motivated largely by a passion to explain to my fellow AI people how our AI concepts had cut us off from an authentic experience of our own lives. I still believe this.

Agre here is connecting the hegemony of cognitive psychology and AI in whenever he is writing about to his realization that “authentic experience” had been “cut off”. This is so Heideggerean. Agre is basically telling us that he independently came to Heidegger’s conclusions because of his focus on “everyday life”.

This binary between “everyday life” or “lived experience” on the one hand and the practice of AI design is repeated often by critical scholars today. Critical scholars with no practical experience in contemporary data science often assume that the AI of the 80’s is the same as machine learning practice today. This is an unsupported assumption directly contradicted by the lived experience of those who work in technical fields. Unfortunately, the success of the Heideggerean binary allows those whose lived experience is “not technical” to claim that their experience has a kind of epistemic or ethical priority, due to its “authenticity”, over more technical experience.

This is devastating for the discourse around now ubiquitous and politically vital topics around the politics of technology. If people have to choose between either doing technical work or doing critical Heideggerean reflection on that work, then by definition all technical work is uncritical and therefore lacking in the je ne se quoi that gives it “ethical” allure. In my view, this binary is counterproductive. If “criticality” never actually meets technical practice, then it can never be a way to address problems caused by poor technical design. Rather, it can only be a form of institutional sublimation of problematic technical practices. The critical field is sustained by, parasitic on, bad technical design: if the technology were better, then the critical field would not be able to feed so successful on the many frustrations and anxieties of those that encounter it.

Agre ultimately gives up on AI to go critical full time.

… My purpose here, though, is to describe how this experience led me into full-blown dissidence within the field of AI. … In order to find words for my newfound intuitions, I began studying several nontechnical fields. Most importantly, I sought out those people who claimed to be able to explain what is wrong with AI, including Hubert Dreyfus and Lucy Suchman. They, in turn, got me started reading Heidegger’s Being and Time (1961 [1927]) and Garfinkel’s Studies in Ethnomethodology (1984 [1967]). At first I found these texts impenetrable, not only because of their irreducible difficulty but also because I was still tacitly attempting to read everything as a specification for a technical mechanism. That was the only protocol of reading that I knew, and it was hard even to conceptualize the possibility of alternatives. (Many technical people have observed that phenomenological texts, when read as specifications for technical mechanisms, sound like mysticism. This is because Western mysticism, since the great spiritual forgetting of the later Renaissance, is precisely a variety of mechanism that posits impossible mechanisms.) My first intellectual breakthrough came when, for reasons I do not recall, it finally occurred to me to stop translating these strange disciplinary languages into technical schemata, and instead simply to learn them on their own terms.

What’s quite frustrating for somebody who is approaching this problem from a slightly broader liberal arts background than Agre did is that he is writing about encounters with only one of several different phenomenological traditions–the Heideggerean one–that have made it so successfully into American academic HCI.

This is where Don Ihde’s work is great: he is explicitly engaged in a much wider swathe of the Continental cannon. In doing so, he goes to the root of phenomenology, Husserl, and, I believe most significantly, Merleau-Ponty.

Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception is the kind of serious, monumental work that nobody in the U.S. bothers to read because it is difficult for them to think about. When humanities education is a form of consumerism, it’s much more fun to read, I don’t know, Haraway. But as a theoretical work that combines the phenomenological tradition with empirical psychology in a way that is absolutely and always about embodiment–all the particularities of being a body and what that means for our experiences of the world–you can’t beat him.

Because Merleau-Ponty is engaged mainly with perception and praxis, rather than hermeneutics (the preoccupation of Heidegger), he is able to come up with a much more muscular account of lived experience with machines without having to dress it up in terminology about ‘cyborgs’. This excerpt, from Ihde, is illustrative:

The blind man’s tool has ceased to be an object for him, and is no longer perceived for itself; its point has become an area of sensitivity, extending the scope and active radius of touch, and providing a parallel to sight. In th exploration of things, the length of the stick does not enter expressly as a middle term: The blind man is rather aware of it through the position of objects than the position of objects through it.

In my view, it’s Merleau-Ponty’s influence that most sets up Ihde to present a productive view of instrumental realism in science, based on the role of instruments in the perception and praxis of science. This is what we should be building on when we discuss the “philosophy of data science” and other software-driven research.

Dreyfus’s (1976) famous critique of AI drew a lot on Merleau-Ponty. Dreyfus is not brought up very much in the critical literature any more because (a) many of his critiques were internalized by the AI community and led to new developments that don’t fall prey to the same criticisms, (b) people are building all kinds of embodied robots now, and (c) the “Strong AI” program, of building AI that is so much like a human mind, has not been what’s been driving AI recently: industrial applications that scale far beyond the human mind are.

So it may be that Merleau-Ponty is not used as a phenomenological basis for studying AI and technology now because it is both successfully about lived experience but it does not imply that the literature of some more purely hermeneutic field of inquiry is separately able to underwrite the risks of technical practice. If instruments are an extension of the body, then that implies that the one who uses those instruments in responsible for them. That would imply that, for example, Zuckerberg is not an uncritical technologist who has built an autonomous system that is poorly designed because of the blind spots of engineering practice, but rather than he is the responsible actor leading the assemblage that is Facebook as an extension of himself.

Meanwhile, technical practice (I repeat myself) has changed. Agre laments that “[f]ormal reason has an unforgiving binary quality — one gap in the logic and the whole thing collapses — but this phenomenological language was more a matter of degree”. Indeed, when AI was developing along the lines of “formal reason” in the sense of axiomatic logic, this constraint would be frustrating. But in the decades since Agre was working, AI practice has become much more a “matter of degree”: it is highly statistical and probabilistic, depending on very broadly conceived spaces of representation that tune themselves based on many minute data points. Given the differences between “good old fashioned AI” based on logical representation and contemporary machine learning, it’s just bewildering when people raise these old critiques as if they are still meaningful and relevant to today’s practice. And yet the themes resurface again and again in the pitch battles of interdisciplinary warfare. The Heideggereans continue to renounce mathematics, formalism, technology, etc. as a practice in itself in favor of vague humanism. There’s a new articulation of these agenda every year, under different political guises.

Telling is how Agre, who began the journey trying to understand how to make a contribution to a technical field, winds up convincing himself that there are a lot of great academic papers to be written with no technical originality or relevance.

… When I tried to explain these intuitions to other AI people, though, I quickly discovered that it is useless to speak nontechnical languages to people who are trying to translate these languages into specifications for technical mechanisms. This problem puzzled me for years, and I surely caused much bad will as I tried to force Heideggerian philosophy down the throats of people who did not want to hear it. Their stance was: if your alternative is so good then you will use it to write programs that solve problems better than anybody else’s, and then everybody will believe you. Even though I believe that building things is an important way of learning about the world, nonetheless I knew that this stance was wrong, even if I did not understand how.

I now believe that it is wrong for several reasons. One reason is simply that AI, like any other field, ought to have a space for critical reflection on its methods and concepts. Critical analysis of others’ work, if done responsibly, provides the field with a way to deepen its means of evaluating its research. It also legitimizes moral and ethical discussion and encourages connections with methods and concepts from other fields. Even if the value of critical reflection is proven only in its contribution to improved technical systems, many valuable criticisms will go unpublished if all research papers are required to present new working systems as their final result.

This point is echoed almost ten years later by another importer of ethnomethodological methods into technical academia, Dourish (2006). Today, there are academic footholds for critical work about technology, and some people write a lot of papers about it. More power to them, I guess. There is a now a rarified field of humanities scholarship in this tradition.

But when social relations truly are mediate by technology in myriad ways, it is perhaps not wrong to pursue lines of work that have more practical relevance. Doing this requires, in my view, a commitment to mathematical rigor and getting ones hands “dirty” with the technology itself, when appropriate. I’m quite glad that there are venues to pursue these lines now. I am somewhat disappointed and annoyed that I have to share these spaces with Heideggereans, who I just don’t see as adding much beyond the recycling of outdated tropes.

I’d be very excited to read more works that engage with Merleau-Ponty and work that builds on him.

References

Agre, P. E. (1997). Lessons learned in trying to reform AI. Social science, technical systems, and cooperative work: Beyond the Great Divide (1997), 131. (link)

Dourish, P. (2006, April). Implications for design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in computing systems (pp. 541-550).

Duguid, P. (2012). On Rereading Suchman and Situated Action. Le Libellio d’AEGIS, 8(2), 3-11.

Dreyfus, H. (1976). What computers can’t do.

Ihde, D. (1991). Instrumental realism: The interface between philosophy of science and philosophy of technology (Vol. 626). Indiana University Press.

Suchman, L. A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: The problem of human-machine communication. Cambridge university press.

Winograd, T. & Flores, F. (1986). Understanding computers and cognition: A new foundation for design. Intellect Books.